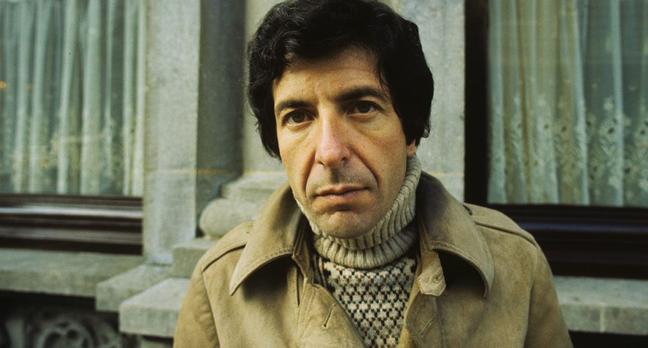

Bruce Eder, a respected popular music critic, once described Leonard Cohen as “fascinating and enigmatic,” a man who could “command the attention of critics and younger musicians more firmly than any other musical figure.”

Yet he also described the late Canadian songwriter as “second only to Bob Dylan” – a view seemingly shared by the Swedish Academy, a Scandinavian Institution which, last month, awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature to Bob Dylan.

But could this have been a mistake? Giving the prestigious prize to a musician has undoubtedly revitalised interest in the awards, but was Dylan truly the best choice? Yes, he may have “created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition” but, when it comes to poetry, Cohen surely has the upper hand.

And for good reason. Cohen, who was born a year before Elvis Presley in 1934, was encouraged by his mother to move into writing at a young age. By the time he graduated McGill University in 1955 with a degree in English Literature, he was a proficient writer, and had his first book of poetry, Let Us Compare Mythologies, published just a year later.

The Canadian went on to write several novels and three more collections of poetry before seriously moving into music. Despite having dabbled in the guitar at age 13 – to impress a girl, allegedly – Cohen’s music had always taken a back seat to his poetry. By the late 1960s, however, songwriting became a natural extension of his poetry, and Cohen rose to the top of the music scene.

Well, almost the top. For Bob Dylan, somehow, has always managed to occupy the niche Cohen carved out for himself. Dylan was hailed as ‘The Bard’ over half a century ago, and his reputation as the poet of popular music remains to this day – the Nobel nod a reminder of how Cohen, at seven years older than Dylan, seems to have had the importance of his contributions overlooked at every turn.

Cohen’s lyrics – remember, the Nobel Prize for Literature focused on Dylan’s words over his melodies – are less an evolution of his earlier poetry, and more a simple continuation. Juggling themes of eroticism, death, redemption and loss, the late songwriter’s reputation as a ‘depressing’ artist stems from his consistent and brazen exploration of these topics.

But there is also a depth to Cohen’s words that outstrips Dylan’s. A dark, dry sense of humour, mocking and self-deprecation runs through the Canadian’s songbook, and the thought that he put into the composition of his lyrics is not only evident in the final product, but in the time it took him to write them.

Bob Dylan, somehow, has always managed to occupy the niche Cohen carved out for himself.

Famously, Cohen was once asked by Bob Dylan over lunch how long it took for him to write biblically-imbued Hallelujah. The songwriter lied and said two years. He then asked Dylan how long it took for him to write I and I, one of Cohen’s favourites of the American. Dylan told the truth – around 15 minutes.

Cohen actually took five years to write Hallelujah. He wrote over 80 draft verses alone during one composition session spent in his underwear in New York’s Royalton Hotel. He reportedly spent this session banging his head repeatedly against the floor. So, whilst Dylan’s lyrics may appear more complex and thoughtful – especially the Dylan of the mid-60s – the time Cohen invested in his work betrays just how nuanced and considered his writings were.

Just read some of the late musician’s lyrics. “I cried, ‘Oh, Lady Midnight, I fear that you grow old, the stars eat your body and the wind makes you cold’,” reads Lady Midnight. “I used to think I was some kind of Gypsy boy, before I let you take me home,” goes So Long Marianne. “I ache in the places that I used to play,” sings the towering Tower of Song.

For the Swedish Academy to say that Dylan ‘created’ new poetic expressions may not be false, but his contributions to the form certain pale in comparison to Cohen’s. The language may not be as flamboyant, or the meanings as ambiguous, but the raw power and sheer honesty of the late Canadian’s lyrics have resonated with fans and critics alike for over half a century.

The language may not be as flamboyant, or the meanings as ambiguous, but the raw power and sheer honesty of the late Canadian’s lyrics have resonated with fans and critics alike for over half a century.

Earlier this year, Cohen penned a moving love letter to his dying ex-girlfriend, Marianne Ihlen. “It’s come to this time when we are really so old,” it read, “and our bodies are falling apart and I think I will follow you very soon. Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine.”

Sadly, this week Cohen passed away peacefully at his home in Los Angeles, but the bigger tragedy is that his contributions to music were overlooked when the first songwriter to win the Nobel Prize for Literature became Bob Dylan and not him. Even a posthumous nod would lose its lustre for coming in second.

It was a mistake, a shame, that Cohen’s lyrics and sentiments were not principally praised for bridging the worlds of literature and music during his lifetime. But, perhaps Nobel’s shortcomings can be rationalised using one of the songwriter’s best metaphors, from Anthem. “Ring the bells that still can ring, Forget your perfect offering, There is a crack in everything, That’s how the light gets in.”

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.