Gordon Ramsay, known as the firebrand chef, now fully embraces being mother hen

For nearly three decades, Ramsay has been largely portrayed as the cyclone of the kitchen. At his new flagship, Restaurant Gordon Ramsay High, all he wants to do is nurture a grassroots movement

You can often tell the quality of a chef not just by their work on the stoves – though that is the clearest indicator – but also by the grade of cooks they produce. Fergus Henderson, the spiritual leader of London restaurant St. John, has overseen a constantly blossoming brigade that’s shaped a coterie of today’s leading names, Anna Hansen (The Modern Pantry, now closed), Lee Tiernan (Black Axe Mangal) and James Lowe (Lyle’s) among them. Thomas Keller, America’s elder statesman of the pots and pans, once gave opportunities to modernist whizz Grant Achatz and Corey Lee, whose three-star Benu is one of the country’s modern greats. The notion of the culinary family tree is briefly alluded to in FX’s wildly successful drama The Bear, in which the fictional fine-diner Ever has a photo wall in recognition to those who once worked in its kitchen and then set out on their own.

Gordon Ramsay, the firebrand British chef with a decades-long career in both the kitchen and in front of television crews, might be recognised as many things – but a paternal guiding light is only a fairly recent addition to his public profile.

Across the years, he’s been the television cyclone annihilating unseasoned chefs who dream of a career in fine-dining. Unless he’s the guy caricaturing himself on social media, uploading on-the-spot reviews of amateur-cooking videos. And when he’s not that, he might be crushing spicy wings on Hot Ones. He will lay out all the faults within a crumbling hotel in Minnesota that he’s trying to recondition. And everyone with an iPhone and a half-reliable broadband connection is aware of the lamb sauce clip.

You get the feeling, however, that Ramsay’s priority is still hardwired to what’s arranged on the plate and how to properly ground his staff in the fundamentals of great cooking. He remains a serious chef – just one who happens to be premium broadcast currency.

“I don’t want to become a tourist attraction. I want to become a destination without the cheese factor,” Ramsay says of his new flagship, Restaurant Gordon Ramsay High, a 12-seat counter that’s 60 floors up in 22 Bishopsgate, and about four-and-a-half miles north-east of the original Restaurant Gordon Ramsay, which still operates in Chelsea. (Ramsay has also placed an outpost of Lucky Cat, his group’s ‘Asian-inspired’ offering, and a culinary academy inside the superstructure, and they’ll be joined by a roof terrace and a Bread Street Kitchen & Bar, another of his casual spots.)

Restaurant Gordon Ramsay High, the chef’s new flagship

At 269 metres above ground, RGR High is Europe’s highest dining room. The view faces out on to what looks like a 4K screensaver, or a landscape designed in post-production for a Ridley Scott feature; The Shard appears like a toy-city miniature; The Gherkin just about pokes into view; you can observe planes make their descent towards City Airport runway. Every so often, clouds enrobe the glass walls. Sunrise, I’ve been told, is an absolute spectacle. At night, you get a blended image of the golden glare from the kitchen lights behind and the gleaming city hinterland in the middle distance.

“To have a showcase of that talent, this high up, is breathtaking,” Ramsay says, gesturing towards a small assembly of cooks who are snipping bits of greens, creating the bases for sauces and brushing dough for the evening ahead.

“Use me as much as I’m using you,” Ramsay, who no longer works the line, advises to those manoeuvring up his restaurants’ ranks. “Because I can’t achieve any more. There’s nothing else left. There’s no other boxes to tick. I’ve seen so many devastating situations [with] burnouts, heart attacks, failed marriages, alcoholism, drugs… there’s so many pitfalls to this level of cooking.”

The view from the counter at Restaurant Gordon Ramsay High

Ramsay himself comes from good stock, having made his bones under chef-giants Marco Pierre White, Albert Roux – “God bless him; what a powerhouse” – and Guy Savoy, a veteran of the French scene.

On the other side, there’s a Murderers’ Row of toques that branch downwards from Ramsay’s position on the tree. There’s Angela Hartnett, the perpetually reliable chef of Murano who’s beloved among old-school creatives for her sophisticated Italian menu. Clare Smyth did time as chef-patron at the original Restaurant Gordon Ramsay, from 2012 to 2016, and now showcases her finesse and elegant handling of British produce at Core, her three-star Notting Hill restaurant. Matt Abe, who has long worked the Gordon Ramsay group’s ladder and who took over from Smyth, is set to depart SW1 to run a solo restaurant where the legendary Le Gavroche resided, with the project expected for later this year.

“There’s a responsibility on my shoulders now to help nurture and push, propel that talent,” he says of his current crop who are extending the lineage. “There’s a responsibility now to continue that sort of engine room.”

One of the leading cooks currently under Ramsay’s guidance is James Goodyear, the former head chef of Evelyn’s Table, on the edge of London’s Chinatown, who now rudders the pass at RGR High.

“He has an ability to make people want to work for him,” Goodyear says of his tutelage under Ramsay, “which is something I’ve not seen in many people at all.”

James Goodyear (left), the executive head chef of Restaurant Gordon Ramsay High, with Gordon Ramsay (right)

This encouraging, tender side to Ramsay comes in sharp contrast with his fiery reputation in working kitchens and the frenetic scenes many have watched on their televisions throughout the years – the shouting matches, the stinging critiques, the wild live services and the meltdowns – but it has been more evident in his shows such as MasterChef Junior, where he takes on the mantle of hypeman rather than gastro terrier.

“It’s always misconstrued”, Ramsay replies when asked whether his passion is often confused with temper. “No, f–ck, I care. And secondly, there’s a price to pay at that level [of fine-dining cooking]. I go back to some of the rigorous tellings-off I got. I f–cking deserved them. I f–cked up, and so I don’t shy away from those mistakes. I own those mistakes. The only promise I had to make to myself was don’t make those mistakes again.”

“When we sanitise things, it makes me so sad, because this industry, at that level of perfection, can’t be sanitised,” Ramsay continues, and criticises a new swearing ban in Formula 1 and how, by contrast, ice hockey players regularly engage in one-on-one punch ups. “I was at an ice hockey game recently; these guys take their pads off and beat the sh–t out of each other, and there’s five-year-olds in the audience thumping the Perspex and punching the wall, because these two grown men are beating the sh–t out of each other.”

“I say it all the time: if you don’t want to work at this level, then don’t f–cking knock on my door”

Cooking – as with driving a fire-breathing race car at 220mph, or carving ice at full throttle – is a high-wire act, with its heat, bravado, roaring vats and often small kitchen confines that have the tightness of a tiny sailing boat. “We’ve got no safety net,” he says of his industry. “There could be the head inspector of Michelin coming here tonight and James overcooks the duck. He’s not going to be happy and high-fiving his brigade at the end of night, he’s going to be pissed. Tension is healthy. Pressure’s healthy. But I say it all the time: if you don’t want to work at this level, then don’t f–cking knock on my door. If you do want to work at this level, then there’s a commitment. But what you get back in return is tenfold”.

Michelin, it must be noted, already did an inspection during the opening weeks – and the duck has seemed pretty spot on so far.

Gordon Ramsay during an interview, in 2001, at his namesake restaurant in Chelsea. Image: Getty

In June, 2024, Goodyear was folded into the operation at RGR, Chelsea, to better understand the DNA of the kitchen and the foundations on which the name is built: sourcing beautiful produce; constantly dialling in on the fundamentals of high-tone French cooking and seasoning; treating ingredients with the care a ceramicist has when pulling creations from the kiln; learning about what Smyth did, how Abe evolved it, and how he might give things his own treatment in this new skyrise setting.

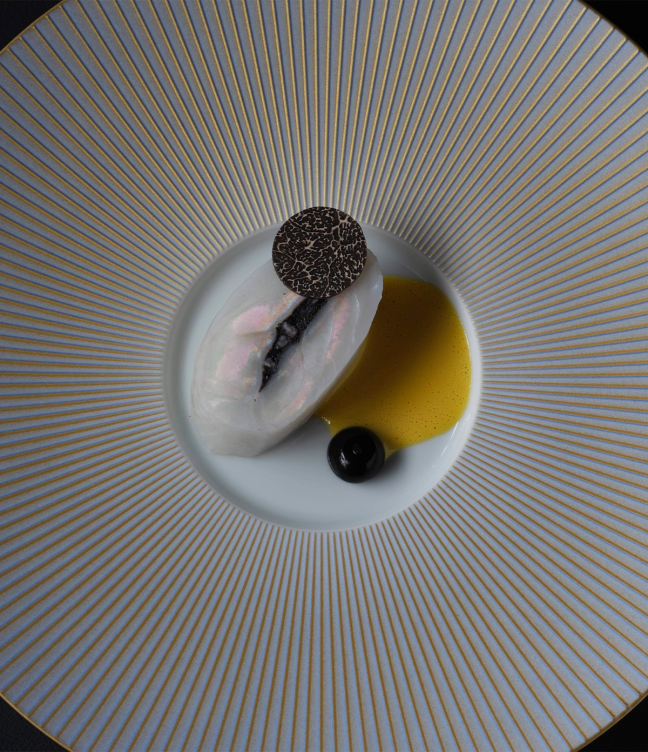

So, depending on how the moons align, you’ll find the classic stamps of seasonal, haute-cuisine dining here. Spears of white asparagus are plucked from the soils of the Loire Valley, dressed with a small garden of fine herbs and beads of caviar, and sweetened with a sauce vierge that makes use of blood orange. The Parker House roll has the curved form of a plumped-up bao bun, and its scent of cooked chives has the sweet, onion-y fragrance that often fumes from a rustic Tuscan oven. That whole Sladesdown Farm duck – a bird that essentially splits the difference between Peking and a gamey countryside breed – is broken down into precise fragments, its flesh a blush of gentle pink giving way to a crisped, charred skin on its outer rim.

Flavour, Ramsay says, is the one thing he wants his chefs to properly learn from him. “There’s a line that we need to stop at – everything’s become very finessed today. But when we go over finesse, then it becomes too picturesque, and we’re losing the balance of the flavour, and then we’re compromising the integrity of the dish, because we want to put one more attractive thing in there.”

“I’ll teach you how to taste first before I teach you how to cook. Because if you don’t understand how it tastes, you shouldn’t be cooking it.”

Sladesdown Farm duck, shown whole tableside, then segmented

If you read between the lines, Goodyear, who did terms in Scandinavia and the Basque lands, areas known for their high-quality yet casual eating, has helped introduce an informal leaning to the place, lowering the firewall that has historically divided the workings of the cooking stations from the cosseted bubble of fine-dining rooms.

The open kitchen here has a calm, lyrical flow and chefs have dialogue with diners – two hallmarks common among Copenhagen’s greatest restaurants. In a very San Sebastián way, there’s a precise, clean, universal appeal to certain compositions, as with the pintxo-size sea bream tartlet that’s slicked with a cream of caramelised pine nut.

Gordon Ramsay in an episode of Kitchen Nightmares. Image: Getty

Being this high up, and opening at a time when his name has already endured for more than three decades, is this Ramsay’s most ambitious project?

“I think it is,” Ramsay says.

He looks back on the efforts that went into opening RGR, Chelsea, in 1998, a period of his life in which he sold his apartment for equity. “That felt harder at the time… that’s all you’ve got.… I felt like I’d lost so much, and then all of a sudden, there’s this noose around my neck to make this thing work.”

But in terms of scale and cost, his latest opening supplants that, he says. “I say the most ambitious – it is because [of] the money we’re spending… We’re investing… It’s a big, big outlay, but, you know, it’s a high risk with a high reward.”

With Michelin having already made its move, it feels a sure thing that the national critics will soon encircle the space. Ramsay, after all, is still a name for headlines.

“I got sh–t for it, but it was the best sh–t I’ve ever had in my entire life”

“I remember A.A. Gill and Giles [Coren] coming in to review Pétrus [Ramsay’s Belgravia, London, restaurant], and we got royally f–cked; royally f–cked on Saturday and royally f–cked on Sunday,” he says of the two British critics. “I couldn’t sit down for three days after.

“I remember when Giles Coren had lunch at Royal Hospital Road [where RGR is located] – he got so plastered, he phoned the next day to actually be told what he had to eat. So, how do I take that stuff seriously?”

In 1998, it was well documented that Ramsay ejected Gill from his Chelsea restaurant, after the writer had taken the cleaver to Ramsay’s previous restaurant, Aubergine. “I knew when I broke away from Marco [Pierre White, with whom Ramsay has had a mixed history], I was going to get absolutely slammed by Gill, and that’s why I kicked him out. It’s irrelevant. You know what you’re going to say in The Sunday Times bears no relevance to me. And secondly, treat my staff like sh–t, then you don’t deserve to be here. So, I stood up for my team. I got sh–t for it, but it was the best sh–t I’ve ever had in my entire life.

“I think the headline [of the Aubergine review] then was, ‘The Failed Footballer that Had a Shotgun Wedding,’” Ramsay continues. “We had two really severe miscarriages, and for any woman and man early on in marital life, that was hard. That was hard. So, what the f–ck has that got to do with reviewing food? It was nothing to do with what we did. I don’t go on those w–nk shoots [with them] where we all turn up for grouse and pheasant shooting. I f–cking don’t want to know any of that. Critique what’s on the plate, please.”

In more recent times, Ramsay has shown softer touches, especially with contestants on MasterChef Junior, where he’s more hypeman than scary head chef. Image: Getty

Though Ramsay may have been crucial in ushering in the age when dining out turned into a sort of middle-class gladiatorial spectacle, with guests hoping to witness a little flicker of heat and anger roaring out from the big-celebrity-chef kitchen, you get the impression that he – though still allergic to stasis – is settled with his life and achievements these days. With the view of London laid out in front, he draws the city’s marathon route – of which he’s done 15 – with his finger, amused when explaining the experience of inhaling the stench of fish as you run past Billingsgate Market on a long, warm day. He enjoys the idea that his mum will “freak” when she dines at RGR High. There’s his emphasis on grooming the next generation, of course. And he also talks about his mentors and the joys of restaurant life with the old-school romance and verve that a boomer literature teacher might have when speaking about Frost, Shelley and Eliot. Pierre White taught him finesse, Albert Roux showed him how to make cheap ingredients taste transcendent, and his move to Guy Savoy’s Paris kitchen helped round out his arsenal.

“I don’t go on those w–nk shoots where we all turn up for grouse and pheasant shooting. I f–cking don’t want to know any of that. Critique what’s on the plate, please”

“It was just one of the most exciting moments of my career, because everything was light,” he says of his time in France. “All the sauces were light and froth. There was no cream, there was no butter. He was finishing sauces with purées of roasted vegetables, purées of dates, purées of basil, purées of tarragon and chervil.”

Ramsay also says he’s more excited than he’s ever been, that he’s less uptight and that he enjoys his success, but – importantly – doesn’t indulge in it. “I’m seeing the fruits of the labour pay off. And it’s been a long slog, by the way.”

The Cornish turbot, served at Restaurant Gordon Ramsay High

The cheese soufflé, served at Restaurant Gordon Ramsay High

In an abstract sense, RGR High’s intention to de-formalise fine dining, whether by design or not, can be seen as a sort of reflection of how Ramsay operates today: the standards remain super regimented, but there’s that approachability and ease to it all. The Cornish turbot with a splash of vin jaune appears like an abstract study of colour and organic forms, but you may also hear Lauryn Hill or The Sundays pipe through the audio system when the dish is placed in front of you. The sommeliers will detail the virtues of the sweet wines they pour, but a few hours there still feels more like dinner than five-star surveillance. The menu is £250 a head (without drinks or tip), but guests are connected by a three-sided counter – and, in such close proximity, they can’t help but gossip with each other about the headlines of the moment and lay out all the pains of their working day. The cooks – a profession once confined to the basement – are working in natural light.

“You look at Mountain and Fallow, what’s happening with these young chefs now, they’re sort of ripping the Band-Aid off, and all the pretentiousness has gone, which is great. Covid taught us all a very firm lesson: just forget the pomp and ceremony, strip the arrogance back,” Ramsay says about this more guard-down, arms-open approach.

“We lost some very good restaurants, sadly. And then the flip side of that is we got rid of all the crap. And so we need this grassroots moment”, he states with intent, referring to Goodyear and co.

“My job is to inspire, create – and get these kids out there.”

- Restaurant Gordon Ramsay High, Floor 60, 22 Bishopsgate, London EC2N 4BQ, gordonramsayrestaurants.com

Want more culinary content? These are London’s best Japanese restaurants…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.